“Go to the bee, and learn how diligent she is, and how earnestly she is engaged in her work; whose labours kings and private men use for health, and she is desired and respected by all: though weak in body, she is advanced by honouring wisdom.” - Proverbs 6:6-8 (Brenton’s Septuagint, 1851)

In the United States, there are documented lawsuits in which farmers sued their neighboring beekeepers for “nectar theft.” I can’t find the reference, but a quick Google search shows repetitions of this folly in our twenty-first century. To us, suing beekeepers for profiting off “our” nectar probably sounds like a complete absurdity, but elements of this prejudice persist to this day. A local farmer here once told me, “Bees are bugs, bugs eat plants. When I see bees, I spray.” I was nearly speechless, learning firsthand how far ignorance extends. Forget about voting. We don’t even agree about honeybees. As I presumed most people knew, bees cannot eat plants — they can’t even pierce the skin of grapes if you place them in a beehive. The delicate mandibles of bees have sacrificed ferocity for artistry: they can mold wax but cannot puncture the thin skin of a single grape.

In the Septuagint, the Hebrew word for ant נְמָלָה (nemalá) has connotations of various insects, is translated as μύρμηκα (myrminka) which can be translated either as ant or bee. No offense to ants, but I personally find the diligence of the honeybee to be a richer spiritual image.

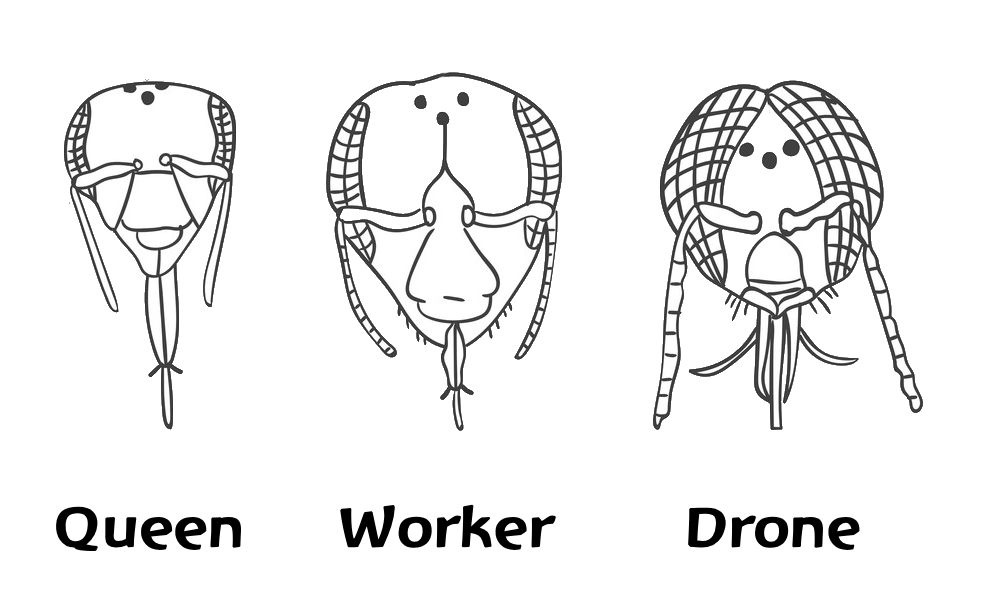

In the beehive, there are two sexes, male and female, but usually only one female is fertile. The sexual activity of bees has been reduced to an almost absolute minimum. “In esoteric language, man and woman always signify the two forces. The man signifies the outer force, while the woman signifies the inner soul.”1 Here, the female queen serves as the “innermost soul,” with the worker bees as the inner soul between queen and drones — neither of which feed themselves but are supplied by the constant striving of the workers. Moreover, one of the chief activities of the worker bees is maintaining an inner atmosphere: “The retention of germ-free nest scent and heat resulting from the naturally constructed comb suppresses bacterial life, hinders the emergence of diseases, keeps the stores digestible and the loss of heat within narrow bounds.”2 Repeatedly tearing open a hive is extremely costly to the bees who must consume their precious stores of honey to restore their inner temperature. Similarly, repeatedly tearing open the boundaries of one’s inner climate with stimulants at unseasonable times taxes the soul enormously in untold ways.

Honeybees only take from the surplus of what plant life offers — what it would not use itself. As the Bhagavad Gita says, “The eaters of the nectar — the remnant of the sacrifice — go to the Eternal Brahman.”3 Our aspiration shouldn’t be extracting all we can from the world or even insisting on moral desserts for our diligent efforts but rather taking only what is not needed by others from the world. Such is the path of the sage and the entire beehive. Even the sagacity of the beehive retains all three aspects: a part that is pure taking, a part that is give-and-take, and a part that is almost entirely generative: the drone, the worker, and the queen, respectively.

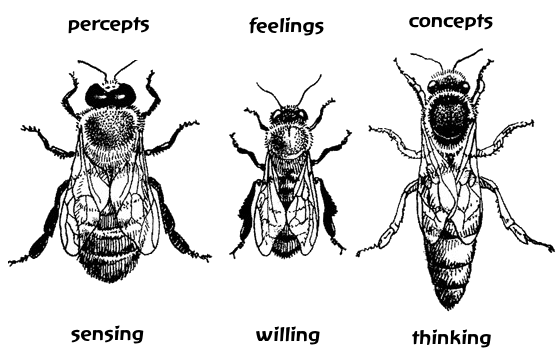

The male drones are oriented to the outer world of sensing, while the female queen is the innermost soul. The communication between these two worlds is the dynamic activity of the chaste female worker bees. Drones with their enormous eyes spread out for many miles, but they do not eat while they are away. Their primitive mouths cannot even feed themselves! Drones must be supplied all their nourishment from the indefatigable worker bees. These drones congregate with other drones from various hives at constellation points where an enormous amount of information is shared, almost like distributed ganglia across the earth’s landscape. Drones are like our senses: they supply information about the external world, yes, but they can never provide nourishment. Drones witness many flowers but collect no nectar. “Man does not live by bread alone, but by every word that comes from the mouth of God.”4 Nourishment must be supplied from within. But when we are addicted to sensual pleasure, we are devoting our inner resources to something that can never offer fulfillment.

As the founder of logotherapy, Viktor Frankl, says, “[T]he pleasure principle is self-defeating. The more one aims at pleasure, the more his aim is missed. . . . This self-defeating quality of pleasure-seeking accounts for many sexual neuroses. Time and again the psychiatrist is in a position to witness how both orgasm and potency are impaired by being the target of intention.”5 It is, paradoxically, by not aiming for pleasure that sustainable enduring pleasure is attainable.

It is the worker bees who feel pleasure or displeasure based on what they desire — what they love with their will. They feel when it is time to swarm and thus begin to restrict nourishment to the queen in preparation for their departure. The workers feel through their refined instincts when it is the right time to exclude drones from the hive in autumn or when to create an emergency queen to replace a fallen monarch. But that is almost too mild: a bee feels pleasure when it finds a flower because the worker bees love their activity. There is no complaining plant and no lazy worker bee. This is true for everything in existence: each thing is the way it is because it loves being that way. An organism’s being is an expression of its loves.

Drones love sensing, and that is their task. Some are made for honor, some for dishonor. Senses are only a problem when they become the sole priority. What the worker bee experiences from the drones or the queen is pleasant or unpleasant based on whether the sensation or the thought resonates favorably with the bee’s essential love. Whenever a life does not correspond to your true love, there can be no real feeling of pleasure. We experience pleasure when a thought affirms what we love. We feel displeasure when an idea threatens something we love.

In human beings, the conscience is never dry, abstract head knowledge nor sticky bodily pleasure but rather the warmth of felt knowing, which is the informed knowledge of the heart. And we will feel pleasure or displeasure in accordance with our loves. If we love the external sensual world, we will find basking in the sun to be enough — like drones. Or if we love the discovery of new ideas, we may stay indoors and contemplate — like an isolated queen of the inner mind. But the test of our lives is other people — the worker bees. No matter how brilliant, how vital with possibility any particular idea is, it must be carried, tended, and enacted by the worker bees. If my idea does not resonate with the host of others — if it causes them mere confusion or displeasure — then it tells me that my idea does not currently align with what the world loves or is not beautiful enough to kindle new love in others. But this still does not tell me whether I am right or the world is right — that can only be considered by thinking through everything the hard way.

Thinking can become a problem, but it is only a problem when thinking becomes uninspired speculation. There are many sterile thinkers who are like laying workers. They were not nourished as fully as a queen — and they were not fertilized by the spirit — but somehow were given more than their proper share, so they continuously lay eggs, but eggs that only hatch into drones. Such thinkers are like Bernard Max in Brave New World: too intelligent to be an Alpha Plus yet not dull enough to be content with his place in life.

A “laying worker” in the realm of ideas expresses a constant proliferation of dazzling but irrelevant concepts, all of which only bend the minds of those who hear them back to sensuality disguised by cleverness, resulting in the further dispersal of inner energy. A laying worker may appear rather like a queen, just as a sophist may appear to be a philosopher, but a true philosopher produces ideas that can germinate, grow, and reproduce. To a drone, the sophist and the philosopher appear much the same — in fact, the sense-bound drone would likely prefer an egg-layer that just produces more drones even though it means the extinction of the hive. The physical senses, like the drones, have no feeling for the longevity of the hive — they seek only what is pleasant to the body. If the senses are given a vote, they would gladly do away with the queen and the workers. Fortunately, the beehive is not a democracy but rather an aristocracy of love. Those who work out of self-sacrificial love for All make the most profound decisions, but for those who follow immediate selfish gratification, even the decisions they do make are inconsequential.

Part of me worries that I myself am one of these insidious laying workers: endlessly producing colorful ideas, but each impotent and always scandalizing people into further distraction. Rather than a lover of truth, am I a mere sycophant of the splendor of the true, a sorcerer’s apprentice repeating habits without life — a fool aping angels? My small hope is that this concern is not likely one that a sophist would trouble himself with. Moreover, just because someone successfully becomes a fully developed philosopher “queen” of the soul does not mean they can then consider all of the workers to be “undeveloped” queens. To see workers as “failures” to realize their potential as queens is absurd because it was the workers themselves whose feelings chose a female egg to groom her to become their queen. The queen could have been any other worker bee, so there should be no special pride in having been crowned.

The worker bees are, collectively, the conscience of the hive. Individually, they do not have the whole picture, but they know what they love and what goes against that. If some ideas seem more popular now, it tells you not that we’ve made progress but what people love now. That’s all it says. A hard heart will love the wrong things, and a heart that loves the body will love things that affirm bodily interests, not intangible spiritual ideals. “[F]aith is never reducible to the consciousness one has of it; that faith is not only, not even first of all, a matter of intellectual analysis (even though it also demands this) but a matter of the assent of the whole…”6 While a worker bee may not be able to articulate her faith (which is her love) in the same way as the queen, it is her entire being.

One thing is certain: though some will be more like one of these three types of honeybees, we each have all three activities in us. And we are capable of development, just as a queen may be created from any worker bee. We are not made to be merely dull drones of the visible, but rather, as Rilke writes:

“It is our task to imprint this temporary, perishable earth into ourselves so deeply, so painfully and passionately, that its essence can rise again ‘invisibly,’ inside us. We are the bees of the invisible. We wildly collect the honey of the visible, to store it in the great golden hive of the invisible.”7

If we live invested solely in how the senses make us feel, that is like a beehive with only drones and worker bees. The destructive nature of laziness corresponds to our attachment to bodily pleasure. A hard worker can become a philosopher, but a lazy person will never become either. We all have a drone aspect, but it must always be kept under control. A sensual person’s identity bound up with the flesh is “‘living on the skin’s surface’ because his consciousness is bounded by the periphery of his own small body.”8 Conversely, Kant famously said, “Thoughts without content are empty,” which is true again in the beehive: unfertilized eggs cannot sustain a beehive. Ideas are not meant to be amassed any more than eggs are meant to be stored up in a beehive: ideas are to be nurtured until they bear sweet fruit for others in practical life.

Someone who lives only in their external senses will only be able to produce more sense-oriented activities without the illumination of the spirit. This is like a beehive with an unfertilized queen or a laying worker. External work without guiding inner light is the “blind leading the blind,” which will continue until it perishes in nothing. As Goethe says, “only that which is fruitful is true.” While drones do most of the sensing of the “real world,” they also do the least productive work. Drones clock the most hours outside the hive, but they do not accomplish even a fraction of the value-creating work. The queen is rarely outside and yet supplies the world with a constant stream of new germinal ideas, each of which changes a little with each incarnation. The worker bee is too busy to bask in the sun or to produce a steady stream of new ideas, but the worker bee feels most strongly the conscience of the hive in all her work. It is she who fights if the hive must be defended. It is she who feeds the young, the queen, and the drones. It is she who saves her sisters. It is she who expels drones to their death when winter arrives. It is she who forbids entrance to a tired old bee whose time is past. The worker bee feels most intensely the special loves of the hive.

A true materialist is not someone who claims that only the material world exists but someone who only thinks in terms of the material world, who loves only sensual things. This can be concealed by clever theological vocabulary or by abstract terms of philosophy, but when the content of someone’s ideas is exclusively bound to what can be enjoyed directly through the senses, a life lived this way exhausts itself in futility. When an outwardly pious person only cares about worldly success and power, it doesn’t matter how well-dressed their materialism may be. Materialism must be differentiated from thinking in terms of analogies drawn from life. A materialistic mind tends to see how everything is different but lacks the ability to see the invisible way in which everything shares an inner kinship. Abstract spiritualism, the counterpart of materialism, merely asserts that “All is One” and considers that enough. All is one, yes, but each thing participates in a distinct way in that oneness based on its particular loves.

As a beehive with a laying worker experiences a rapidly growing number of drones without workers to replace what is needed, the materialistic way of living is ultimately self-negating. A house divided against itself cannot stand — therefore, we do not need to fight evil with any of its methods. We need only watch — and save those who wish to leave the divided house of war. Without worker bees, it doesn’t matter how much drones hum about because they cannot collect honey or lay eggs.9 A life bound up with external action and sensing favors the proliferation of energy-consuming drones without the nectar supplied by the workers.

Thinking is difficult work: extracting from what we can sense directly the nectar of experience and concentrating it as spiritual honey takes constant effort and sacrifice. The idea that thinking should be easy is as absurd as demanding that building a house should be easy. If all we care to do is feel how externalities affect us, we are telling our inner beehive that the workers no longer need to harvest honey — as if drones are all we need. Such a mentality aspires towards hiding from the lessons of life. Thought is necessary, but it can never be alone. As Fritjof Schuon says somewhere, you can have bhakti without jñāna but never jñāna without bhakti. Without devotional love, anything we call “knowledge” is superficial. If we don’t love what we are learning, then we are using it as a means to an end that we do love. If we don’t know what our goal in learning something is, then the answer is probably unconscious selfish power, which is simply Mammon.

As Sebastian wistfully says in Brideshead Revisited, “If it could only be like this always – always summer, always alone, the fruit always ripe…”7 But it is in the winter of contemplation that our lessons are assimilated, not during the summer of sensuality. When autumn arrives, the celibate worker bees drive the drones out of the hive to perish. Similarly, in meditation, we withdraw our vital energy from our peripheral nervous system and turn inwards. What we experience when we go into the darkness of meditation is what occurs in autumn:

“With joy I can experience

The autumn’s Spirit-wakening:

The winter will arouse in me

The summer of the soul.”10

Fortunately, even people who claim to be materialists are usually more involved in the spiritual world of thinking than they might realize. A consistent materialist wouldn’t even use the term and would deny the existence of personality, character, or a reality that isn’t mere labels.

“May I be spared the objection that communists also sometimes die for their Marxist-Leninism! Because if they do so voluntarily, it is not for the dogmas (concerning the supremacy of the economy, the ideological superstructure, etc.) that they have, but rather for the grain of Christian truth which takes hold of their hearts, namely that of human brotherhood and social justice. Materialism as such does not have—and cannot have—martyrs; and if it seems so, then those whom materialism accounts as such, truth to tell, bear witness against it.”11

To know something truly is first to love it and only then to know it. “That which we experience within ourselves only at a time when our hearts develop love is actually the very same thing that is present as a substance in the entire beehive. The whole beehive is permeated with life based on love.”12 To know something truly is for such knowledge to be fruitful, as Adam “knew” his wife — knowledge less intimate than this is abortive.

Winter is a time of introspection. The sensory drones die back, and the intensity of inner warmth increases. In humans, our skin grows cold, but our core warms up to maintain our temperature. With our attention withdrawn from the periphery during winter, there is a natural tendency to enter into a state of contemplation. Imagine watching the coursing “blood flow” of the farmer’s movements from overhead in fast-forward: the movements are more lively in spring and summer, and more constrained by autumn and winter. Steiner says that the blood carries the “I” — and so we see the farmer as the organizing I-principle of each distinct farm. There is an “I” for every beehive.

Anyone who’s kept hives will be able to see the differences in personality between one hive and another. One is gentle, another cantankerous, and another furiously busy. The philosopher Aristotle describes the changing sounds that hives make when they are preparing to swarm, so we have good reason to conclude that he was a man who had direct experience with bees. Though each individual bee does not have the complexity to express personality, there are more neurons in a large hive than in the human brain. There is enough emergent complexity within a hive to embody true aspects of living personality.

As we “digest” our experiences from the day during our sleep, so we metabolize our summers during our winter reflections. Any attentive gardener will be making notes to herself about what worked and what didn’t — as well as resolving about what to do better in the coming season.

“In the life of the bee everything that in other creatures expresses itself as sexual life is, in the case of the bees, suppressed, very remarkably suppressed; it is very much driven into the background.”13

In the beehive, we have an image of how the human being should operate within itself. We should not be fixated on how senses make us feel but rather on the moral dimension of the meaning of what those feelings convey. Feelings by themselves are devoid of meaning. For example, I can train a dog to bite strangers by rewarding it each time. Such a dog will grow up feeling like a good dog simply because of conditioning. Conversely, I could punish a dog by hitting it with newspapers. Such a dog will develop the feeling of fear for newspapers, even though newspapers themselves never really did it any intentional harm. Feelings are facts, yes, but they do not tell us what those facts mean. Only thought can interpret feelings. If we refuse to do the painful work of thinking, we are merely living according to our evolutionary prejudices, the programming from our upbringing, and the echo chamber of our own ego identity. A life led merely by feeling avoids what is uncomfortable and seeks what seems easy — but what if you were a dog taught that good was bad and bad was good? How could you know without thinking? Thus, our aspiration should be to become like a beehive, whose life consists in collecting and containing the libidinous nectar of flowers while at the same time suppressing their own sense of bodily pleasure. Instead, they find meaning in their work, which is not mere bodily pleasure but something that approaches a subtle but pervasive joy.

“If I say of an observed object, ‘This is a rose,’ then I express nothing at all about myself. But if I say of the rose, ‘It gives me a feeling of pleasure,’ then I have characterized not only the rose but also myself in relationship to the rose.”14

Uninformed feeling is adrift just as sensual pleasure is meaningless, and abstract thoughts in isolation are unproductive. The Luciferic temptation is to ideological purity: clear ideas severed from practical reality. As Charles Péguy writes,

“It was a pride in thinking, a poor pride of ideas.

A pale pride, a pale pride all in the head.

Smoke.”15

Our feelings tell us what we know: we are either in a right relationship with the world, or we aren’t. These feelings are facts, but what do they mean? I can be angry with someone, but they could be totally innocent. Feelings alone don’t accurately tell us whether I am in the wrong or the world is in the wrong. This is where thought must be employed to interrogate our hearts and illuminate them with higher principles. If it turns out that, yes, this conforms to the highest principle I can conceive, then do as St. Paul says, “Be angry but do not sin.”16 In other words, good luck with that!

What is pleasant to us (or unpleasant) tells us what we value: “pleasure has value for us only as long as we can measure it against our desire.”17 Someone who finds thought to be unpleasant will dismiss those who perform the arduous work of thinking. Conversely, someone who is lost in abstract academic thought — who never has to do anything with his ideas — may be tempted to dismiss laborers as meaningless. But what we denigrate merely says what we do not love, not what is valuable.

When we die, we cannot take our body with us. Instead, we take the mature egg-laying queen, seasoned workers, and a wealth of honey. When we die, it doesn’t matter what it is we value ourselves. Death does not ask for our opinions.

When a beehive produces a swarm, a major portion of the available honey is taken along with many of the oldest bees and the old queen. This is like reincarnation, where something of the feeling and individuality of the former life is carried over into a new body. In human beings, this is usually rather different, though Isaac Bashevis Singer captures an image of how reincarnation works with bees in one of his short stories:

“Transmigration of the soul doesn’t occur only after a man’s death. Sometimes it takes place during his lifetime. The old soul leaves him and a new soul enters.”18

And so, an old soul leaves the beehive, and a new queen is inaugurated. In my experience, after such an event, the entire personality of the established hive may change. In reality, each time a hive swarms, it should almost be given a new name — because the original individuality has absconded and a new one has been introduced. There is obvious continuity: the new queen is the daughter of the old queen, but personality traits can vary dramatically between daughter and mother. One could even imagine a seasoned queen founding not just one additional hive, but two or three during her journeys. What wisdom she carries with her wings!

As Gunther Hauk writes, each new swarm does not rob the hive at all: it is an “act of love.”19 The vast majority of resources are left behind. To make a single pound of wax, it takes bees eight to ten pounds of honey. Yes, the swarm takes a major portion of the liquid capital, but they bequeath all the infrastructure to the future. Imagine a farm where the aging farmers take most of the money in the bank, some of their favorite old cows, and move to a new retirement location — while leaving the fencing, the buildings, and the herd for the new caretaker. Such an act could only be considered a selfless act of love, because they hand over their entire life’s work to someone else.

May we all learn to be like the humble bee in our own souls and in the entire world.

R. Steiner, Concerning the Astral World and Devachan, pg. 172

Johann Thür, Beekeeping: natural, simple, successful

The Holy Geeta, Swami Chinmayananda, pg 317

Matthew 4:4

Viktor E. Frankl Anthology: Edited and Annotated by Timothy Lent. United States: Xlibris US, 2004.

Louis-Marie Chauvet, The Sacraments, xix

Rilke, Collected Poetry, pg. 316.

Paramahansa Yogananda, God Talks with Arjuna, commentary on Chapter 2, verse 3

This is the fundamental problem of communism: materialistic minds in charge of the direction of society can only drive it into the ground, because they explicitly deny the reality of inspiration from the spiritual world and the significance of the imagination.

Rudolf Steiner, tr. Isabel Grieve, Calendar of the Soul, Week 30

Valentin Tomberg, Meditations on the Tarot, pp. 355-356

R. Steiner, Nine Lectures on Bees

R. Steiner, Nine Lectures on Bees, Lecture I (GA348, 3 February 1923, Dornach)

R. Steiner, Intuitive Thinking as a Spiritual Path, pg. 55

Charles Péguy, The Portal of the Mystery of Hope, pg. 56

Ephesians 4:26

R. Steiner, Intuitive Thinking as a Spiritual Path, pg. 235

Isaac Bashevis Singer, A Crown of Feathers, “The Recluse”, pg. 237

Gunther Hauk, Toward Saving the Honeybee