As you may know, all these posts go out for free. There’s no paywall. But if you like what you read, it doesn’t hurt to pay to subscribe. The only benefits to doing so is that: 1. you pay my phone bill, and 2. you get to comment on my posts.

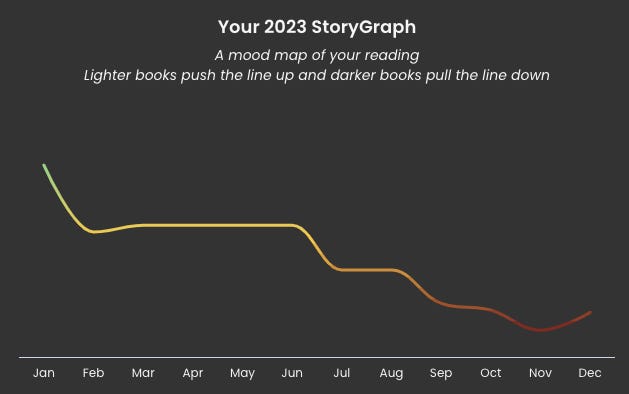

I like to track my reading with StoryGraph. It’s a better version of Goodreads with charts. For anyone still languishing on Goodreads, but desiring better analytics, you can export your Goodreads data and StoryGraph is there to take it into the future.

According to StoryGraph, I read 8,428 pages over 23 books. This isn’t a big year for me. Now, this is only what I remembered to document — and only books. Articles and essays don’t make it into these numbers.

As always, I read a wide range of things. Kabbalah, Eastern Orthodoxy, Catholicism, Hasidic stories, Tibetan buddhism, theosophy, and more. It’s impossible to make a short summary, but I’ll try to keep it organized. One book that can’t really be recommend, but that I have been reading (slowly) is the Philokalia. I’m on volume two.1 It’s about monkish life, asceticism, and prayer. I can’t recommend it for beginners, though The Mountain of Silence is a decent start for the Orthocurious.

The Outlier

The MANIAC by Benjamín Labatut, my Chilean doppelganger, is a splendid exploration of the lives of people influenced by one genius sociopath who helped give us computers, AI, the atomic bomb and championed M.A.D. (mutually assured destruction) as a viable way to navigate the nuclear threat. It’s a novel, but most of it is full of facts. In a way, this kind of historical fiction — carefully researched, yet embellished. I’m reminded of George Saunder’s splendid book Lincoln in the Bardo, not because of stylistic similarities with Labatut but because I sense an inner kinship to giving a human face to the facts.

About a fascinating man with very little empathy, this book culminates in our current era, where artificial intelligence is making strides previously considered impossible — even beating world-class Go champions. But, as with anything in this world, even AI seems to have a certain Achilles’ heel perhaps. A pleasure to read, and I’d even suggest hopeful.

I find this conversation to be beautiful. Maybe it’s just that he’s on my wavelength, but to me it’s wonderful. He urges us to reconsider many older ideas, even God. He strikes on things that speak deeply to me such as when he says “reality is hallucinatory” which approaches ideas of Kabbalah: the logic of the world is not linear causality. The world obeys the logic of a dream. How would we live lucidly in a dream? Still asleep, but awake (however fleetingly) to a higher plane of awareness?

Most Buddhist Read

This book is about Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche going walkabout. Privileged from birth, he was raised like a little prince. A benign naïvete informs each page. The author not only doesn’t know what he’s doing, but doesn’t even seem to be able to tolerate the mildest of discomforts at first. But who knows what the promise of marriage entails? Who knows what any project will cost them when they begin? But like anyone leaving their father’s house, this story has hope. As a microcosmic Siddhartha, he leaves the fortified walls of his protected childhood, and, belatedly, tests the world. He fares poorly, and nearly dies.

But think of what caused an existential crisis in Siddhartha: seeing an old woman, a sick man, and a corpse. For ordinary people, these are everyday occurrences. For a protected prince, these are shocking anomalies. With some beautiful passages, I respect the Tibetan buddhist idea of “adding wood to the fire” — of cranking up the difficulty in order to burn through attachments all the faster.

Favorite Read

Cardinal Hans Urs von Balthasar is known for many other things, but I stumbled onto his work in a reference to Love’s Mind by John S. Dunne (as well as The Mystic Road of Love by the same). I found Love’s Mind with a reference in the Ezra Klein Show in a discussion with Maryanne Wolf entitled “The Reading Mind.” When I tried to purchase Love’s Mind, almost all copies were sold out — or exorbitantly expensive — which shows the remarkable influence that Ezra Klein’s show has. So I waited a few months, and, sure enough, lots of affordable copies showed up. Perhaps when people realized it wasn’t erotic but about mystical solitude, they sold their copies. As a muslim woman exclaims to the Catholic author of Love’s Mind, “you are in love with ayasofia!”2

Balthasar’s Heart of the World is poetic, angst-filled spirituality that represents the real human existential struggle. Only later did I see that the afterward to Valentin Tomberg’s Meditations on the Tarot is written by none other than Hans Urs von Balthasar.

Rilke wrote in his Duino Elegies, “For beauty is nothing but the beginning of terror, which we still are just able to endure, and we are so awed because it serenely disdains to annihilate us. Every angel is terrifying.”

If Rilke were a better theologian — and perhaps a lesser poet — I imagine he might write something like The Heart of The World. Bypassing the howlings of self-actualization and following one’s psychotic “true will” Hans Urs von Balthasar says, “Do what you will, you remain a captive of love.”3 This is a book I could read only a few paragraphs at a time, because it sang with such truth. If I were to underline it, almost every sentence deserves to be remembered.

Weirdest Read

I can’t say that I love Philip Roth. But reading Operation Shylock: A Confession was stimulating. Philip Roth stars as Philip Roth in his own novel and yet there is a doppelganger who is impersonating him but whose birth name is also… Philip Roth. If that weren’t an odd enough premise, this “other” Philip Roth proposes that the modern state of Israel is the number one threat not only to the survival of the Jewish people but also the biggest threat to world peace. Needless to say, this book was not well received. The author becomes entangled with Mossad, but we learn little other than that Roth is called an artist of disinformation. One then asks: with the resurgence of support for the state of Israel after this book was released, one might wonder if that had been the point all along.

As the world seems to be playing out these days, one might wonder whether Roth’s lookalike was right.

First Read

The first book I read in 2023 was The Secret of the Rosary (148 pages) by St. Louis de Montfort.

Several people I know have died recently, which turned me to prayers for the dead in the second half of 2022. This meant employing the rosary. One day, I cast aside my buddhist mala — whatever spiritual path I’m on will have beads — and searched for the rosary I’d purchased a decade ago at the Vatican Museum. I found it, and, having it my pocket for the first time, in my mind’s eye felt a sphere of empty space around myself and a torrent of gray serpentine tendrils of smoke swirling on the outside. Knowing what gray and black mean from Annie Besant’s Thought-Forms, this suggests to me that fear and malice were not merely jettisoned but no longer permitted entry into this protective field.

If that weren’t enough, I traveled for work where I met an old friend, Frances, who herself inexplicably said she had been looking for her rosary all day. Not knowing she had a rosary, she said, “My rosary! I can’t find my rosary!” I took out mine — hesitantly — which she snatched up to pray. That was day one. It was also strange enough to show me that this wasn’t nothing. Realizing that I could participate in a confraternity (which ostensibly grants a “plenary indulgence” of which I could use countless), and so I did:

“If someone desires to become a part of a Rosary Confraternity and is of a different faith, yet is known to be one who believes and would like to practice the prayer of the Holy Rosary, for my viewing of the ancient and current statutes, I cannot find anything which would prohibit such a good thing as someone desiring to join.”

But, as with many things you begin halfheartedly, you may end up becoming Catholic anyway. I’m part of a two-year study group reading through Valentin Tomberg’s Meditations on the Tarot. But that’s a story for an entire other post.

Since I won’t be going back in time to 2022, here are some that I read leading up to 2023:

True Devotion to the Immaculate Heart of Mary by Robert J. Fox

In the Redeeming Christ by F.X. Durrwell

Ordered by Love: An Introduction to John Duns Scotus by Thomas M. Ward

The Mystical Christ by Manly P. Hall

The Complete Mystical Works of Meister Eckhart

The Cloud Upon the Sanctuary by Karl von Eckharthausen

The Seven Storey Mountain by Thomas Merton

Lazarus, Come Forth!: Meditations of a Christian Esotericist by Valentin Tomberg

Final Read

The last book I read in 2023 was The Notebooks by Simone Weil (648 pages). There are few people I’ve read who so closely correspond to some of my own thoughts, sometimes almost exactly my own thoughts. While I can’t agree with everything she says — such as “the Beast is society” — a radiant light shines through this work.

He took me into a church. It was new and ugly. He led me up to the altar and said: ‘Kneel down’. I said ‘I have not been baptized. He said ‘Fall on your knees before this place, in love, as before the place where lies the truth’. I obeyed.

He brought me out and made me climb up to a garret. Through the open window one could see the whole city spread out, some wooden scaffoldings, and the river on which boats were being unloaded. The garret was empty, except for a table and two chairs. He bade me be seated.

We were alone. He spoke. From time to time someone would enter, mingle in the conversation, then leave again.

Winter had gone; spring had not yet come. The branches of the trees lay bare, without buds, in the cold air full of sunshine.

The light of day would arise, shine forth in splendour, and fade away; then the moon and the stars would enter through the window. And then once more the dawn would come up.

At times he would fall silent, take some bread from a cupboard, and we would share it. This bread really had the taste of bread. I have never found that taste again. He would pour out some wine for me, and some for himself- wine which tasted of the sun and of the soil upon which this city was built.

At other times we would stretch ourselves out on the floor of the garret, and sweet sleep would enfold me. Then I would wake and drink in the light of the sun.

He had promised to teach me, but he did not teach me anything. We talked about all kinds of things, in a desultory way, as do old friends. One day he said to me: ‘Now go’. I fell down before him, I clasped his knees, I implored him not to drive me away. But he threw me out on the stairs. I went down unconscious of anything, my heart as it were in shreds. I wandered along the streets. Then I realized that I had no idea where this house lay.

I have never tried to find it again. I understood that he had come for me by mistake. My place is not in that garret. It can be anywhere—in a prison cell, in one of those middle-class drawing-rooms full of knick-knacks and red plush, in the waiting-room of a station—anywhere, except in that garret.

Sometimes I cannot help trying, fearfully and remorsefully, to repeat to myself a part of what he said to me. How am I to know if I remember rightly? He is not there to tell me.

I know well that he does not love me. How could he love me? And yet deep down within me something, a particle of myself, cannot help thinking, with fear and trembling, that perhaps, in spite of all, he loves me.”4

If you like obscure philosophical minutiae, self-abnegation, and algebraic musings, this is perhaps for you.

Longest Read

Edging out Simone Weil for the longest book read in 2023 is The Glories of Mary (672 pages) by St. Alphonsus Liguori

I don’t have quotes to share from this, but this work (plus others) expound how Mary is not a mere woman among women but Womanhood itself, Motherhood itself. Moreover, she is Wisdom incarnate. After all, who but Sophia could hold the Logos in her womb and not be destroyed? Who else could be the Ark of the Covenant? Mary is the voice of Wisdom in the Old Testament, the deep waters over which the Spirit hovers in Genesis. It is she our souls must become one with in order to conceive the Christ within. As Angelus Silesius says, “Christ could be born a thousand times in Bethlehem — but all in vain until He is born in me.”

After all, who but Sophia could hold the Logos in her womb and not be destroyed?

Other notable Marian books I read include:

Mary: Mother of the Son (3 vols) by Mark Shea.

The Secret of Mary by St. Louis de Montfort

Slowest Read

The book that took the longest to finish was A Crown of Feathers by Isaac Bashevis Singer, Nobel laureate who wrote his stories in Yiddish. I would read a story, then set it aside. These are stories to be savored like fine wine.

Singer writes of demonic possession, of transmigrating gilgulim, of the whispers of the devils and our ancestors, and stranger beasts. These are delightful stories with dreadful characters and puzzling endings, all of which seem to provoke a sense of awe at the incomprehensible complexity of life and of God. While both Singer and his brother Israel Joshua Singer were raised under the influence of his Hasidic rabbi father, Isaac wandered from those roots without losing the belief in the sitra achra — the sinister “other side.” Israel, the rationalist, went a very different direction. But we are here to talk about Isaac Bashevis Singer.

Demonic entities in Kabbalah have various names, but one is Qlipphoth (קְלִיפּוֹת) which are literally “shells” — husks left behind from a formerly living process. As a cicada sheds its former shell, but leaves behind something that nonetheless has grasping claws, the qlipphoth are like leftovers of creation who, by right, should really nothing but black earth by now. The qlipphoth are empty, parasitic, and always hungry. Qlipphoth are “mad, bad, and dangerous to know” (as Lady Caroline Lamb described her lover Lord Byron) to such a point that even to name them is considered taboo in Kabbalah. For the names of these entities attracts them, much like calling out to God by name (or Mary and all the angels). An image of fragmentary shells — words without meaning — are staggeringly dangerous. As they say in Dr. Who, “an image of an angel is an angel.”

These are like the astral haunts left behind when someone dies and their spirits move on, but qlipphoth are much worse. We pray for the dead so these shells will move on. To pray them into the light, as is done at every Mass, is to condemn such demons to the all-consuming fire. As Friedrich Nietzsche warns us, “Battle not with monsters, lest ye become a monster, and if you gaze into the abyss, the abyss gazes also into you.”5

Aharon of Karlin said, “it is not a sin to be sad, but sadness can bring on the greatest sins.” And this is why evil cannot be combatted with evil: you simply become the evil you fight. This is what “turning the other cheek” means. It looks like foolishness to the world because it is a refusal to become evil. It is better to die quietly and good — like a lamb led to the slaughter — than to bring Mordor home. We must always fight evil always indirectly: shrewd as serpents and innocent as doves. When we go at it head-on, we become the very evil we oppose. Why? Because whatever we resist we strengthen, as weights in a gym strengthen the muscles they weigh down. Therefore, as Christ says, “Do not resist one who is evil.”6

If we wish to oppose evil, it is not by killing it, but by using Aikido, a martial art that allows your opponent to make any move he desires, exhausting himself — and then, at the last minute, instead of employing a killing blow, using a graceful “saving throw” to render the spent opponent unharmed.

Likewise, we cannot combat melancholy by talking about it or fixating on it. The solution to the abyss does not lie in the abyss. We must look to the light if we wish to overcome darkness.

The solution to the abyss does not lie in the abyss.

Though this goes beyond the scope of Isaac Bashevis Singer, I feel compelled to bring up that God is one who is “of purer eyes than to behold evil, and canst not look on iniquity”7 which is to say, God is blind only to pure evil because evil is an unreality. He knows everything that is inasmuch as being is good. But to God, from God’s perspective, nothing is out of order. If I desecrate the imago dei, I become less visible to God because I become less godly. You could really almost say that the demons inasmuch as they have become less real have become more invisible to God. Instead of standing forth in their full glory, demonic entities are translucent, less substantive, and therefore also less visible. Inasmuch as they have any being at all, they have goodness, and therefore remain clear to God’s gaze.

Gershom Scholem, who transformed Kabbalah into a respectable field of secular academic study, references Isaac Bashevis Singer’s literary work in his magnum opus about the antichrist figure Sabbatai Ṣevi:

“Of the whole gamut of Lurianic teaching concerning retraction, the breaking of the vessels, and restoration, only those elements that stressed man’s personal struggle with distinct and, as it were, individual qelippoth became actually and vitally meaningful. But the mystical task of annihilating particular qelippoth presupposes an exact knowledge of the nature and name of the qelippah concerned. The result was an extraordinary growth of weird and bewildering demonology for which, in our time, I know of no better illustration than that displayed in Isaac Bashevis Singer’s stories. The demonic side of the world cast its shadow on all the manifestations of human life in a manner unparalleled in other kabbalistic traditions. The reader of the literature of seventeenth-century Polish kabbalism is confronted with legions of qelippoth erupting from a strange mythological universe that cannot be found in earlier texts.”8

In short, the modern world is full not only of demonic entities but more and of greater variety and fiercer tenacity than earlier times.

Most Jewish Read

After Isaac Bashevis Singer and Philip Roth, can you get more Jewish? Well, I’d say yes. Other books I read which merit their own description in full include:

The Sabbath by Abraham Joshua Heschel

The Soul by Rabbi Adin Even-Israel Steinsaltz

Four Hasidic Masters and Their Struggle Against Melancholy by Elie Wiesel

Souls on Fire by Elie Wiesel

Messengers of God by Elie Wiesel

Somewhere a Master by Elie Wiesel

Elie Wiesel is known for other things, but his Hasidic stories are splendid. Rich with contradiction, paradox, and heart, this is the human experience in all its honesty. Here doubt comingles with faith, mercy and justice kiss.

2024 is looking no less Marian. I am currently reading, among other things:

The Black Virgin: A Marian Mystery by Jean Hanni

The Sacrament of the Present Moment by Jean Pierre de Caussade

The Radiance of Being: Dimensions of Cosmic Christianity by Stratford Caldecott

Wise Men and Their Tales: Portraits of Biblical, Talmudic, and Hasidic Masters by Elie Wiesel

A prayer from St. John Bosco:

O Mary, powerful Virgin, you are the mighty and powerful protector of the Church; you are the marvelous help of Christians; you are terrible as an army in battle array; you alone have destroyed every heresy in the whole world.

In the midst of our anguish, our struggles, and our distresses, defend us from the power of the enemy and at the hour of our death, receive our souls in paradise. Amen.

Ἁγία Σοφία in Greek, Ayasofya in Turkish: “Holy Wisdom” or Sophia herself

Hans Urs von Balthasar, Heart of the World

Simone Weil, The Notebooks, vol 2, pp 638-639

Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, Chapter VI

Matthew 5:39

Habakkuk 1:13

Gershom Scholem, Sabbatai Ṣevi: The Mystical Messiah, pg. 82.